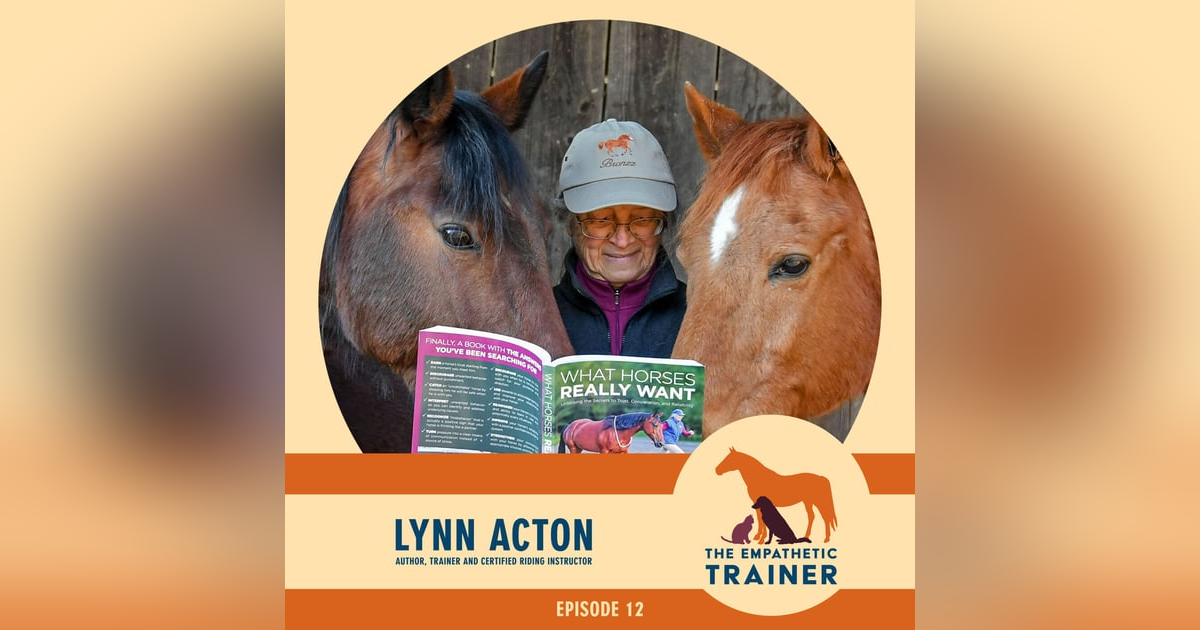

Lynn Acton - Alternatives to Dominance Based Horsemanship - S2 E12

Tune in to hear Lynn Acton, acclaimed author and horse trainer, share practical tips on how to build trust and connection with your horse. Learn about the basics of earning trust, using clear body language, moving away from dominance based training, and understanding horses' emotions. Lynn also talks about being a protector leader and what horses really want from us. Get simple and actionable advice for creating a strong bond with horses and keeping them happy by avoiding unnecessary stress. Whether you're a horse enthusiast or just curious, Lynn's down-to-earth wisdom makes it easy to connect with these amazing animals.

https://www.empathetic-trainer.com/

And Remember, Animals Just Want to be Heard.

00:14 - Understanding Horses From Their Perspective

09:10 - Protecting Horses and Shifting Perspectives

13:26 - Positive Reinforcement Training With Horses

25:36 - Building Trust and Curiosity With Animals

29:18 - Building Trust Through Body Language

36:58 - Horse Emotions and Trust-Building Techniques

51:32 - Key Principles for Interacting With Horses

01:04:25 - Horses and Humans

01:08:40 - Social Media's Impact on Online Engagement

Hi, I'm Barbara O'Brien. I'm an animal trainer and photographer, and I'd like to welcome you to the Amphithetic Trainer. Hello, I'm Barbara O'Brien and you're listening to the Amphithetic Trainer. Today's guest is Lynn Acton. Lynn Acton is an author, horse trainer and certified riding instructor. Her book what Horses Really Want Unlocking the Secrets to Trust, cooperation and Reliability is a must-read for any horse person who wants to do better for their horse. Lynn believes the key to a good relationship with your horse is putting yourself in their shoes to figure out what they need from you. Well, I couldn't agree more, lynn, and we're really happy to have you here with us today. Thank you for being on our show. That's my pleasure, barbara. Well, I'm a big fan. Let me start right there. I have your book. It's kind of beat up because I've read it.

Speaker 2:

That's ridiculous.

Speaker 2:

More than once, and so we're certainly talk about this, but I wish we had lots of time because all the great stuff that you had to share with us, I just think horses are going to be better for it, and so we're grateful that you put it in a book form and that also people can follow you on social media and communicate with you and clinics and everything that you do. So we're grateful for that. So again, thanks for being here. Okay, so, with horses, I love that a little bit of breed buys here, but you're Arabians. I just want to start with Arabian. I've had Arabs and I love them.

Speaker 2:

I was an Arab horse groupie back in the 80s when I was a teenager. I'd go to the Region 10 horse show at St Paul, the hippodrome in St Paul, at the fairgrounds and like walk around the barn and go do you need help? Can I brush your horse, can I? And people took pity on me and would let me brush their beautiful show Arabians and work with them and so really have a soft spot for them. So reading your book because you talk about you Arabians a lot was a joy, because they don't tell anybody, because I have all Morgans now but I still think Arabs are, like some of the smartest horses out there.

Speaker 1:

I think there's a lot of similarities nice similarities between Arabians and Morgans. I have to tell you the funny story behind this is, before I got bronze, I said I will never, ever have an Arabian. Everything is a spooky airhead. I had that bias and I was horse hunting and I looked for two years and I was not finding anything and somebody finally said, oh, just go look at some Arabians. I know a good breeder, he has a lot of good horses, and I met bronze and I watched his interaction with his breeder and I watched how athletic he was and I thought that is the horse I've been looking for all my life.

Speaker 1:

So you never pay to have a breed bias. It's the individual horse.

Speaker 2:

Oh, you know, that's really, really true, although I'm kind of biased with my Morgans right now, but I've always had Morgans too. I like both breeds equally well. Just a side note, because we were talking about how wonderful Arabs are. I have four sons and many Mises, and back in the it must have been 90s, when horses were quite expensive like they are now I had the girls who were teenagers young teenagers write letters to breeders saying do you have a retired show horse that we can give a wonderful home for? Because we couldn't afford to buy horses, like you know what people needed for them at the time. And so we ended up with quite a few dollar horses. I think we ended up with four or five dollar horses.

Speaker 2:

So my Mises rode and showed them in 4-H and my sons had the pleasure of riding Arabs. And so we had a wonderful horse named St Croix Ramallah, who was a region I'm sorry, in the nationals. He was in the top 10 of Western pleasure and he was retired to us and we had him at the rest of his life and you could not have asked for a better kid's horse. I mean, he was the kindest. Well, his name was we call him Reno and he was the kindest, best boy you know. And then I had a retired show mare. Mercedes loved her, so so much a hard horse there. And then my other son, or we had another horse, kijiba, who was also a national champion in his retirement. So they came with a lot of experience but kind, kind hearts. So they were great, great kids horses.

Speaker 1:

I was going to say that was the best model for kids to grow up with. The boldest, bravest riders I know grew up riding horses that they trusted would take care of them, and that's just a great way to get a kid set up for confidence and skills.

Speaker 2:

Oh, it's really true. And now I have grandchildren, and they're getting to be, you know, starting to get old enough to ride, you know. And the best, most fun part, though, is my youngest grandson, who's two is decidedly horse crazy, and I'm just thrilled because he comes out and he goes horse. And it's like we have to go horse.

Speaker 1:

So hopefully we catch one or two. This is the last role that grandkids come visit is we have. We have horse time, Exactly You're the cool, cool grandma for sure. Right, yeah, I think so, yes.

Speaker 2:

Okay, well, I'm going to start off with. I want to talk about your book. I'm going to hold it up again what horses really want, which we'll talk where people can find that as we get to the end. But there's a quote that you talk about. When riding and training my horses, I was forever trying to put myself in the place of the animal and to think from his point of view. So how did that come about? So I'm going to start from when you were young and what your experience was like with horses when you were young. Like tell us the beginning, and did you always feel that way, or was there a shift, you know, as you became more aware of horses and their feelings?

Speaker 1:

I always felt that way. As a young child, I was encouraged to be empathetic toward animals and think about their point of view. And then, when I was old enough to read Colonel Podyski's books and I saw that quote from him I thought that that really sums it up. If you look at things from the horse's point of view, it makes everything so much easier because they have emotions. They have feelings and if you understand what the feeling is behind their behavior, then you can get to the heart of what's going on and then you can end up with a relationship where you have a horse who wants to be your cooperative partner, rather than a situation where you're trying to drum obedience into them. So I was.

Speaker 1:

I always had a natural empathy for horses, and as a kid and I think a lot of young women feel this way I had the feeling that I sort of understood what they felt, and a lot of us are taught then well, but they don't have feelings. And that was that was really scientific view back in the 90s of well, animals don't have feelings, it's all about instinct and conditioning. Well, as a kid I knew they had feelings and I tuned into them and I think that really helped me get along with them better, so that that is why I love that quote from Colonel Podyski is if you think about things from the horse's point of view but then you end up being cooperative partners instead of having this boss-servant sort of relationship.

Speaker 2:

Oh, absolutely, I have the book. I have a couple of his books, so I know what you're talking about. That's pretty cool. Let's start. How did you get into horses? Did you get? Were you lucky enough to grow up with them, or?

Speaker 1:

Yes or no. I was horse crazy from the time. I knew what a horse was like, like so many of us, and the only option I could find for riding as a kid was a horse dealer, an elderly horse dealer who let kids ride horses in return for doing a garden chores, and so it meant I rode whatever horses were there. I got very little instruction. Just what some of the older girls told me so very much I had to figure out for myself by coordinating with the horses and by reading whatever I could find, and bless those librarians. My school and community libraries had the best books on nonfiction books on horses, especially Margaret Cable Self, who was the great horse maker, you're speaking my language.

Speaker 2:

I have several of her books too, treasures.

Speaker 1:

Yes and yeah, and horse mastership was like my reference and so I learned a lot from reading and then I just tried it out on the horses and it got to ride a lot of different horses. So that was a very different education than kids get these days, where most of their riding is supervised. Mine was completely unsupervised and I did some amazingly stupid things and oh yeah. And it's great if the horses for the fact that.

Speaker 2:

I'm still here. Yeah, no, I was really. I had an elderly woman that had a farm and I exchanged riding not even riding lessons, just the opportunity to ride for chores. And we were just like every Saturday we do morning, we do chores in the morning and we get to ride all afternoon. And like she didn't even come outside, we were able to just go and do and, of course, we learned how to ride bareback and we probably weren't as thoughtful of those horses as we could have been looking back as a teenager, but they would let us know if we'd gone too far. You know, if we were going too much, they'd stop dead, we'd look, flying off. And you learned like, okay, maybe you're not thrilled with, you know cantering this much. So we learned like, you know, okay, we should be a little more sensitive about your feelings. So yeah, exactly, I do feel like we were kind of lucky in a way, because we certainly got a lot of confidence and you know we're able to be very confident riders. So that part was a good thing.

Speaker 2:

But, and no helmets, nothing like that. I'm really grateful for things like helmets. Nobody wore helmets in those days, no, but I'm grateful because I did have a serious fall on an Arabian mare not her fault at all. She was telling me no, really, I had her way over threshold. This is before I knew what I know. Now I'm trying to get smarter every day about things and and got bucked off. I was riding bareback with a halter and got bucked off and broke my pelvis in three spots, but I'm long recovered. This was back in 2020. But the helmet is what protected me from like really having a serious concussion, because I know I landed hard on my head.

Speaker 1:

I had quite a few concussions, I suspect as a kid, and decided I really don't need any more.

Speaker 2:

So we are in agreement, we are pro helmet, pro helmet. Everybody wear your helmet, Okay, All right. So I'd like to talk to you about kind of the theme of your book, which is protector leadership. Do you want to kind of run through that a little bit? For for people that may not, you know, a lot of our audience is going to be new to horses or have horses, but new ways of thinking about horses, because I feel there is a real shift going on about dogs and cats and horses and dogs have been there for a while but the shift in how we're thinking about horses, where we are understanding that of course they have feelings and of course they're going to act like horses and the more we know about that the better. So maybe you can run us through that a little bit.

Speaker 1:

Well, the difference is that traditionally, horse training has been focused and especially with the introduction of natural horsemanship, very much focused on what we want horses to do for us and how we can make them do what we want. How do we get them to perform better, how do we get them to behave better, how do we get them to stop spooking? And it's all about what they do. It's about moving the feet and controlling the behavior, and it completely ignores that all behavior is prompted by emotions. Emotions are there to help a species survive, so they control the behavior. And if we look more at the emotions behind the behavior, then we can elicit cooperation and even devotion from horses who really want. What they really want is to feel safe, and I discovered this. I mean, I think most of us kind of intuitively know this and in spite of some of the training techniques many of us were taught I think a lot of people, especially women, tend to be more empathetic and nurturing, and so, in spite of the techniques we're taught, a lot of us have attempted to make that emotional connection with a horse that helps a horse feel safe, but nobody that I could find in any of the books that I read really looked at it directly from the point of view of let's look at the emotions and meet the horse's emotional need and make that the integral part of our relationship, our handling and our training. And what pushed me way into doing this? Because I was kind of working around the edges of it I got a foster pony. I said I told the rescue I'll train him so he can be more, train him for riding, so he can be more adaptable. And he came and they said he was a good old boy. We pony kids off of him and do all kinds of stuff. And he was anxious and anxious horses are not safe horses. So I tried what I thought was a really radical experiment. Said you look at him cross-eyed and he's like, oh no, oh no, what did I do wrong? So I tried what I thought was a really radical experiment. I said I'm going to use as much positive reinforcement as I know, I'm going to cut back. And well, the results really stunned me. They kept meeting me at the pasture gate every day like, oh hi, I'm glad to see you. And there was no regression. I thought horses were always supposed to regress when you were training. There was no regression, there was no resistance. I did some click and treat with him, but after a while he didn't even bother looking for the treats. I clicked to say, hey, you did that exactly right. And he's like, oh good, what do we do next? Oh, yes, for sure. It actually was like I'm waiting for this guy to blow up because this is just too good to be true, way too good to be true. So something's got to go wrong. Right, and I was actually nervous about riding him for a while, but nothing went wrong.

Speaker 1:

And after eight months the first prospective adopters came to meet him. They adopted him and off he went and they said, well, something really interesting happened here. But was it just him? Did I just have Pony Einstein, who was just like, so smart he got everything from your phone. I got to find that.

Speaker 1:

So I called the rescue and they said what a tougher pony to train next time. She said, oh, I know, just pony for you. So I went to meet her and the nice lady at the rescue turned Brandy loose in their big arena so we could meet her, and then she couldn't catch her. This is the lady who fed and cared for this pony for three years, and the mere presence of my husband and myself as strangers had Brandy so terrified that she wouldn't even let her familiar person catch her. I said, ok, there's something more to this than what I thought. So when she got my concession, was getting frustrated and embarrassed and I said how about if I see what I can do? Because catching a horse is kind of a specialty of mine. Because I don't catch them, I left them to catch me.

Speaker 2:

That's there you go. There you go Before let's. Let's explain that, because that is so true. I don't catch them, I let them catch me. That is a really great principle. If you could just go into that, we'll continue the story about Brandy. But how does that work? Because everybody, a lot of people, have trouble with catching the horses or being caught.

Speaker 1:

I tell them that I'm not going to pressure you. So I stand very quiet, put my head down, just sort of relaxed and slouchy, and after a while running around and around, she started looking at me like oh, you're not chasing me, you're not trying to catch me. And when she looked at me, I backed up a step.

Speaker 2:

And that said to her.

Speaker 1:

I'm not going to pressure you. I saw you look at me and asked me to back up. So I did. And every time she looked at me I backed up a step and then after a while she started to slow down. I backed up another step.

Speaker 1:

Every time she did what I was hoping for the looking at me and the slowing down I backed up a step and after a while she slowed down and started watching me like well, you're kind of a strange person. People don't usually do what you're doing Exactly. And after it was 15 or 20 minutes she just walked over to me. I didn't touch her right away because that would have been a pressure again and spoke to her like so I just stood there and let her stand in front of me and then I kind of turned carefully and stood next to her so she and I were facing the same way Reached up, scratched her neck she didn't go away, but I figured that was enough. She said, okay, I'm done, and I walked back to the gate where my husband was standing with the director of the rescue and Brandy followed me.

Speaker 2:

Yes.

Speaker 1:

And I thought this is interesting. She's really connected. And for the next half hour we talked about plans and what to do about Brandy, and for the entire time she stood there next to me and I thought I don't know what to do with this, because if you just look at this horse, it's pressure. How do I train with no pressure? How do I handle the horse with no pressure? You know, I'd gone with the first foster pony, I'd reduced it, but this time I had to use none. So I really didn't know what I was going to do with her. But she was still standing there next to me, looking calm, and I'm thinking I can't just leave her, I have to try. I have to try, I can't leave her. So I said, yep, this was fall. I said yep, bring her to us in the spring. And I had all winter to go. Okay, what the heck am I going to do now?

Speaker 1:

So I pulled together all of my backgrounds with horsemanship, which it was very varied. I grew up riding hunt seat, I've ridden in the Western, I've done a classical massage that's, massage for horses, not the ribbons. I've done musical freestyle. So I've learned things from all those different places. And then I have an academic background in sociology and system science. So I kind of pulled that together my horsemanship, information and background and research and started looking at what did other people do when faced with a horse like this.

Speaker 1:

Kim Warns talked a lot about the gray goose and how he was a problem for everybody and even for her at first, and what she did to work with him. And Frederick Peñón of the Cavalier talked about Tumpado, his very difficult so ended up being one of the stars of his show. So I got a lot of philosophy. Everybody could explain the philosophy of you just don't pressure on the horse Well, yeah, but then what do you do with them? And nobody was explaining how to implement this. Like, yeah, yeah, I'm all on board with the philosophy, but how do I go about doing it? They really got really lucky. When we delivered our first foster pony to his new home, there was another pony there who was absolutely petrified of people. I mean so petrified that when we looked at her over her stall door she plastered herself to the wall in terror.

Speaker 1:

A couple months later I heard that a young trigger was working with her and doing really well. I said I got to see this. So he graciously gave me the demonstration. He walked up to the pony's stall door and stood sideways to the pony not facing her but sideways and just held the holder and after about five minutes she came over and let him put the halter on her head. He said the first time it took him half an hour just standing there waiting and then, with the halter on her, he walked out the door, down the barn aisle, across the driveway into the indoor arena and she was plastered to his side like an obedience dog at heel and the lead line never went tight. He went.

Speaker 1:

When they got her in the indoor he took the lead line off and she continued to follow him everywhere. And I was thinking well, how did he teach her to do this? He didn't. It was all in his body language. He made himself a safe place to be by not pressuring her. He didn't approach her, he let her approach him and so he became a safe haven for her and after a while he took the lead line off. She kept following him and then all of a sudden she left, zoomed off around the arena, ran around a little bit, started playing with poles and poke her nose into this, that and the other thing. I thought, okay, he's getting embarrassed if this lapsed, right. So I said what are you doing now? He says nothing, she'll be back. Okay, well, pretty soon she poked her nose into something. It fell over. She scared herself. She ran back and she plastered herself to his side, just like a full runs back to mama and plastered himself to her side. When she scared here's my say that's when the light bulb went on in my head. She gave her the choice to leave. She never felt trapped, she never felt pressured.

Speaker 1:

Then I had a clue where to start with Brandy, and that's exactly how it worked. When Brandy came, I'd turn her out in my arena. I thought, well, if I turn her out in my three acre pasture, I might not catch her for a whole hail. This would actually look good. So I put her in the arena and then I would go and work in the arena. I pull weeds or rearrange equipment and she'd watch me and then she'd leave off grazing. And the next thing I knew and this was only a couple of days she had her nose in the middle of whatever I was doing, I'm cool. She's like, can I help you with that moving equipment, like can I check this out with you? And so she wanted to be with me. She started following me around.

Speaker 2:

And this was because there was no pressure. Not asking her to do anything at this point. You're just building a relationship by not using pressure.

Speaker 1:

Exactly what horses really want is to feel safe, and a horse who has been traumatized has learned that people are not safe, and that had been Brandi's experience. She was found wandering loose feral here in upstate New York where we're not supposed to have feral horses, and so she had to be trapped and herded onto a trailer to be taken to the rescue. So there's trauma. And then she went to a dominance oriented trainer for 30 days training and I suspect that pretty much did her in, because he was the one who delivered her to us and we could. She was absolutely petrified to him so we had that to overcome. So she needed some time to be satisfied that people might be safe. But I was lucky she decided pretty quickly that I was safe and then that began to extend to other people.

Speaker 2:

I was gonna ask you about that, if it extended, yeah.

Speaker 1:

And I don't know what makes the difference, because some horses will find somebody they feel safe with and that's it Then. Maybe it's just because the other people around them don't give off safe vibes. But once Brandi got to know different people here, I was the main person who handled her and my husband would come in the barn and engage with her, but he was a dog person before he was a horse person, so his whole approach to animals is just as very friendly. Hey, would you like some scratchin' and some patin' in each other? That's my husband as well. Yeah, yeah, and it's great for making a nice connection with the horse. So from Brandi's point of view it's like, okay, it looks like everybody here's safe and kind of by a natural selection process, anybody who comes to our farm likes animals, so I think that vibe goes over to the horses. Right now we have a repешь Life, but I have to say that as a new lonely and friend for me it's a wonderful feeling.

Speaker 2:

For me, it's a pretty special feel of it. It's the same when I was at home, I mean as family. You came out and I was all away from home to spend Christmas with. I don't get no car.

Speaker 1:

All I understand is youPer Lavive lives a positive history, that I wasn't going to pressure her and that made me a safe person, safe place to be, and that's really what horses want. And she showed that the very first day that I met her at the rescue farm, when she was willing to come over to me and follow me to the gate and wait there with me. So sometimes you see that with the horse immediately. Other times it can take a while, especially if horses have known a lot of people that were not trustworthy and they've just sort of decided basically the human race is best avoided, and so then it can take longer.

Speaker 1:

If you have a horse that's interesting and the horse might go investigate it and that sort of triggers curiosity, which is a positive feeling, and if you're associated with something positive like that, then that's points in your favor or you go investigate something new Maybe there's treats involved too, or little bits of choice hay or something and then the horse gets curious. So if you have a horse who's just plain avoiding people now Brandy clearly wanted to find somebody to trust and she said Lynn, you're it, but other horses will just plain avoid, and in that case you need to make yourself interesting or engage in something interesting that arouses their curiosity, and if you're associated with curiosity and being able to investigate things and maybe discover fun treats or a toy to play with, then that makes you become an appealing person to be with.

Speaker 2:

It's very effective Because we are mammals, animals, mammals the same as horses and other animals. It's as an animal actor trainer which is my main job. It's very, very true, because sheep respond the same way as a horse would Like. If you run up to a flock of sheep that do not know you, of course they're going to scatter Because you're a threat, you're tall, you're a human, they don't know you. But if you go in and you stand and you wait and you're quiet, I find that the sheep are curious and they're going to come.

Speaker 2:

They're going to come slowly as long as you're not making threatening moves Because you are so interesting and you find that with cattle I mean cattle are dangerous to the point of curiosity, because I've learned a herd of cattle can be very curious and then they'll push to get into you because they really want to know you're there. So you got to be careful with cattle. And then children. If you are quiet and respectful and interesting, instead of going like baby, children will come around because now they're like and you're very interesting.

Speaker 2:

And of course we all know this about cats If you do not pressure a cat and glom onto a cat, he's going to come to you and that's why people go. I don't like cats.

Speaker 1:

Why is that cat coming here?

Speaker 2:

Because you are so interesting giving off that vibe. Yeah, so it's very, very true. I was going to talk a little bit just quickly about the three mustangs Keep calling them mustangs because they are on the range, but they were my mordans that I got from Westwood Mordans out in Montana who lived on the range. The two yearlings were super people oriented. Even though they hadn't been handled much, they've been well cared for. They were raised and heard on the range. They are super friendly, like right there, always wonderful.

Speaker 2:

But the one that came as a four-year-old that had a lot more time being more worried about everything around her and her environment and not having a lot of human contact. And it took several weeks of just quiet exactly what you're talking about Quiet curiosity until she would come and put her head in a halter on her own will. And it's taken months, a whole season, because I've had her a little over a year now to work with such quiet presence, quiet presence so that she's starting to trust me and it just takes time. But I feel like as we go through this process this horse will climb a tree for me, like we are in such tune with each other because I don't push her, I don't pressure her. I let her decide what she wants to be with me and work on things together. And it's so gratifying Because I was going to send her back.

Speaker 2:

In the beginning. I was like she's so anxious, so anxious and after getting hurt on that prior horse, I didn't want to get hurt again and I can't trust her. But now that we're building all this, it's so gratifying. So I understand how you felt about Brandy when it finally did click. How gratifying that must have felt and we can talk some more about that.

Speaker 1:

Well, I started using my body language. Well, I was already using my body language, of course, right from the start, but then I started asking her to walk with me and using synchronization or copying, which is something that young horses will play with themselves, and Phillies in particular play games of like let's move in step. And so when I walked because I had to lead her to and from the barn for daily turnout and everything but I would make sure that we were walking in step so that we were matching steps and if I speed it up, she'd speed up, If I slowed down, she'd slow down, and so I could lead her with a loose lead and there was no pressure. Now, you might say that asking her to move with me was some sort of pressure, but it was something that she was comfortable with, and so that was how a lot of her ground training went. Was I never used pressure on a halter or lead?

Speaker 1:

I used my body language to say let's go here, let's go there, and I would signal turns and I would use my voice for walk, trot, halt back up. So she was learning those by association, but she was mostly learning them what I wanted by watching my body language and she's very subtle. If I wanted her to back up, I would just lean my body back a little bit. She's like oh, OK, we're going backwards now and turn my shoulders, Like OK, we're going to go this way, we're going to go that way. So she naturally yeah, we were kind of naturally coordinating.

Speaker 2:

Well, horses are wired to read body language, obviously, because otherwise they run into each other in the herd. When they're running, they run into each other, so they have to know that space and horses are really as you know. Of course, horses are very subtle, with just the tilt of a head and ear to tell another horse back off or no, you're welcome to come play with me, or anything that they're trying to communicate. And so, of course, our favorite heart horses, the ones that we love the most, are the ones that read us the best, even if we didn't know what we were doing. But they were so accommodating and just a shift of a hip bone we would turn, like they would turn before you think turn because they're so in tune with you. And what a great relationship. And they had horses like that before I knew what was going on. I was really blessed that way to have those. Of course it wasn't great.

Speaker 1:

I think they tend to be pretty subtle. I think most people don't realize how much most of us use body language. That's very much at odds with what horses are interpreting it, as Horses are so subtle. I had taught Brandy as we moved along and I started using more hand signals and voice commands. I taught Brandy to back up if I tapped the ear with my finger and that was working. What she was beside me and then when she was in front of me, she wasn't backing up. No matter what I did, she wasn't backing up and I finally realized I forgot to lean back. The finger didn't mean a whole lot, but my body had to be in the right position, and the thing about this is that we don't get to decide what the right answer is, and this was where making this shift for me was a huge, huge leap of faith, because you can't say the horses disobeyed me. When you're using body language, you need to think in terms of that's how she interpreted what I did. So when I stood there and tapped the ear with my finger and she didn't back up, she wasn't being disobedient, she was doing exactly what she understood. I said, which was nothing when I leaned back, then she understood. So for me this was a whole process of discovery and I would have to say, ok, I did this and Brandy did that, not the thing that I thought I was telling her to do. So, ok, so that's how I say that it's like going to a foreign country. You don't tell them how they're going to speak their language. You have to figure out how to speak in the way that they understand you. And that was the process I was going through with Brandy, and she's so subtle that horses see all kinds of things that we don't realize we're doing. And then we also need to interpret the body language that they use in terms of the emotions behind it.

Speaker 1:

We went for a walk one day. I was taking Brandy up the driveway. We were just going to take a little walk down the road. Well, the recycle bin had been spilled I think raccoons partied that night or something and there's stuff all over the place and from the bottom of the driveway Brandy could just see this mess up there and she didn't want to go. But she didn't turn to pull me back to the barn. She body blocked me and I couldn't get around her to go up the driveway and show her look, this is really OK, honey. Instead, she had me body blocked. I couldn't go up there. So fortunately, I saw my husband. I called my husband. I told her what was going on. I said can you go up to the recycle bin and show Brandy that this is safe? And she watched. And she watched and she let me go first. And eventually we got to the top of the driveway and then I started picking things up and putting them back in the recycle bin and she had her nose in the middle of it. It's like, oh, let me inspect this thing, let me inspect that thing. But the thing about her body blocking me is that she was in my space. She was pressed against my body and a lot of people would have said, oh no, she's in your space, she's trying to dominate you, she's trying to tell you what to do. She was trying to keep me safe. Lin, that's something's not right up there. We should not be going up there and I don't want you getting hurt either. So you stay down here where we do it safe. So we need to really be careful about the interpretations A lot of people have been programmed to interpret based on dominance theory, which says horses want to be dominant, so they're always trying to tell you what to do and if you give them half an inch, they'll take a mile, and that's not what's going.

Speaker 1:

On Horses having. We were talking about emotions earlier and different mammals reacting similarly to horses. All mammals share the same seven core emotions. That is like a whole podcast in itself, which is, in its top-ranked, absolutely fascinating and anybody who wants to pursue this, absolutely yes. Two great resources are watch Rachel Bedingfield's videos on the seven core emotions or signed up for one of Carolina Westlin's online courses. She has a couple of great free short courses on animal emotions and when you start understanding what's going on with them emotionally, it explains so much behavior and it shows that they really do only want to have cooperative relationships with people, because horse herds unlike that big myth horse herds do not survive on dominance, on a dominance hierarchy. They survive by cooperation. Right, and everybody looks out for everybody. The adults are responsible for the kids. Everyone looks out for each other and so once they connect with us, they look out for us, and I've heard some incredible stories of horses looking out for their people, even when it meant a horse putting herself in danger.

Speaker 2:

Right. Do you remember the story about the in Canada? I believe it was in Canada in the mountains. A woman was leading a trough ride of tourists and a grizzly came out of nowhere and was charging the boy on a horse, you know, and her horse, like I think, if I remember the story right, just leapt in between and knocked the grizzly over. If I remember like, ran into the grizzly, totally not what horses would do, but to protect the other horses and the tourists in the girl riding, like she drove the horse. It's big gelding, drove the horse or drove the grizzly away, completely against what horses do around bears, I mean. Normally they're going to be like we're gone.

Speaker 1:

But that's the protective instinct. So that's why I ended up calling our role being a protector leader, because when we show the horse that they're safe with us, that sets up that mutual social bond that horses have in a natural herd. And once they feel that bond, then this protection becomes reciprocal. I protect my horses, they protect me, and this has become Brandy's Brandy's role in our herd. She's a she's her self appointed protector in the herd and if she thinks something is wrong she lets me know.

Speaker 1:

She saw my, my grandson one time laying face down in the snow. Well, he's from Virginia. Snow is a great novelty. He was having fun. She didn't know that she saw his inert body face down. She ran around the barn to where I was doing chores, winning frantically, and it was there. She wanted me to follow her. This is like the end of a TV show Follow me, lynn. You've got to come with something really, really wrong. And I had. And so I talked to my grandson. I said you need to tell Brandy you're okay. And he talked to her, but she was not satisfied until he got up, walked into the paddock and give her a big hug. Then she was like boy. I thought something was really wrong there.

Speaker 2:

Right, no, you're. That's a great story. What a great horse. Yeah, I my, my Rita, the mayor I was talking about that was anxious, who you know. Day by day we're getting better has.

Speaker 2:

You know body of things that she does. That if the wrong person was around, it would misinterpret, because I've discovered that, because first we started working through the fence when it came to handling her body, and parts of her body was through the fence for her safety in mind, because she was so reactive she would whip her rear end around and threaten to kick. You know, there was always this threat that I'm going to kick you. And so instead of disciplining her, punishing her for a natural instinct when she was worried, I would just work through the fence instead and let her on her own terms. Let me touch her and handle it. Well, I discovered she loves to have her butt scratched. I mean that sounds awful, but you know she loves to butt by her tail and her thighs and her scratch. It's just like heaven, heaven. And so she learned that, wow you, if you threw the fence, you're scratching me. Now you can handle my back hooks through the fence, you know, because she's her butt's right up against the fence, because she would rub on it and I go oh, you want your butt scratch. So over time, she learned that that's a great reward.

Speaker 2:

And so now, when I, now, when I'm working with her, we're not using the fence and I'm just when I say, okay, we're going to just hang, we're just going to be here together, she will. She will turn, whether she's on a halter or not, like I'm doing chores, or she will turn and put her butt to me, which is her language. Oh, please, let's play that game. This is my favorite. But if you didn't understand that her, where her, her ears, her eyes, her expression was soft, why she's turning her butt, if you didn't understand that, you know you'd be hell God, I'm my space. Well, you know it would change everything. So, so I'm, I am careful to be like I'm deciding to do this, we're doing this together, instead of like you can't just always, you know, come and like, knock me down or something. We're going to allow that safety like you talk about. But we have a relationship and now, for a long time, people will go like well, why couldn't you just do it?

Speaker 2:

But for a long time she didn't want to give her back feet, and so how could we have the failure to trim her back feet if she didn't feel safe enough in our new, you know, in her environment to pick up her back feet? So we, she's learned that scratch, scratch, scratch, scratch, scratch. I'm going to ask for your foot a little bit, thank you, she gives a little bit. Go ahead, give her the foot back. Scratch, scratch, scratch, scratch, scratch. Can I have your foot, please pick up a little bit, scratch, you know.

Speaker 2:

So it's like something pleasant happens when we pick up those back feet, and so now over time I mean it's spent a lot of time rewarding but she's learning that it's perfectly safe to give me those feet. And I've got a wonderful trainer. I'm working with a young gal that she was on my podcast, tiffany Stoffer, who was a Liberty horse trainer, and so there's a lot of asking yes questions, and so Rita's learning that these are good yes questions and that we're not going to pressure her to do something that frightens her, upsets her, makes her feel reactive and defensive. And so what? Your, your book has talked all about that, and that's where we, you know it started to get like crack open for me, you and other trainers that I've been following a whole paradigm of how to think about horses.

Speaker 1:

And working through the fence is a great idea because it does give the horse the freedom to move away. And if you're not working through a fence, then you have to just be extra careful to watch the body language and not provoke the fear. And Brandy, of course, had some very big issues about having different body parts touched. And this is someplace where a lot of people go wrong. They first meet a horse and they want to go in and touch the horse all over. And we've been told you know there's, there's trainers that say, well, you, the horse, should allow you to touch and if not, well then we'll have them do laps in the round pen. And that's not earning trust. That's proving that you are not trustworthy, because you haven't really given the horse a choice. You've put them between a rock and a hard place Either allow touching I'm not comfortable with or I have to run laps. This is not a person I want to be anywhere near.

Speaker 2:

It sounds like a terrible first date. You know right, it's a terrible first date. I'm going to grab you and touch you all over. You know like, excuse me.

Speaker 1:

So yeah, so I did with Brandy the same same thing. You did just a little bit different construct, because I wasn't working through a fence, I didn't, I didn't sense any well. I think I was able to read her body language well, enough that, and she was very clear in her body language. So it's like okay, you can touch my shoulders and my withers and a little bit of my back, but don't touch my ears, don't go behind me. She had an absolute terror of somebody going behind her.

Speaker 1:

So we did, we did butt scratching from the side, but I just worked to it, always looking at where's her anxiety level, and as soon as the anxiety went up, I backed off and right, the common wisdom is oh well, then you're rewarding her for getting anxious. You can't reward feelings. Feelings are what they are. You don't encourage the feeling by by rewarding it. What I was saying to her when she got anxious was I see that you're anxious. I respect that. I'm not going to pressure you and scare you. And so, after many of these, these incidents where she'd start to worry about something, it's okay, we don't have to do that right now. Back off, we'll go back and scratch the bottom of the score, the withers or whatever. Wherever you want scratch now, we're cool. I want to touch your hind legs, but okay, we can only go as far as your flank. That's all right. We'll come back to that another time and that that is all telling the horse. This person is trustworthy.

Speaker 2:

And it takes time. Right, I mean it takes time like this doesn't happen in two days, I mean, unless your horse gets shut, is shut down and is blocking out every experience, or or so anxious that he appears shut down and then explodes.

Speaker 1:

Well, yes, and a lot of times when people think they've got a bomb through force, what they've really got is a time bomb, that horse, who, who has been shut down. So what they've done it, what's happened is that you're no longer going to see the warning signs of anxiety. They've been 20. Don't show the warning signs of anxiety. Okay, so I'm going to hold it in. I'm going to hold it in, and that's when they blow up and you can get there with with food too.

Speaker 1:

By accident, I my husband's mayor was was very pushy about food and it's funny. My vet said we'll try clicker training and I'm like what that's it? How's I going to help with food? But of course it did, because it taught her oh, if I want food, I have to do something to get it. So she figured out for herself if I stand at attention, I nicker. Okay, I'm going to treat, but I don't get a treat if I'm mugging somebody or leaning over and crying, I grab the food from them. So she learned to stand still really, really well.

Speaker 1:

So the first time I was going to put a blanket on her, I gave her the signal to stand still. She's standing still, standing still, I'm getting the blanket out and I didn't see until the last minute. I'm already to fling the blanket up over her shoulders and I realized she is vibrating with tension, absolutely vibrating. And if I had thrown that blanket over her I have no doubt she'd have exploded and we'd have had 1100 pounds going every which way. And I'd been in the middle of it when I saw that I said wait a minute, put the blanket back. I said okay, shiloh, let me explain to you what we're going to do here. And I folded the blanket and then we went through a slow process and 10 minutes later the blanket was on, she was calm and now you can fling a blanket anywhere, but you have to watch when horses starting to get anxious, and if you miss those early signs and they blow up, that's not the horse's fault, that's that our failure to watch the body language and before warned.

Speaker 2:

Oh yeah, no, when I was sitting on that mare who I'd been working with, climbing on her bareback from the fence, she was trained, she'd been trained. The Arab mare that I got hurt on she'd been trained and stuff like that. But it had been a while and then she'd had some bad experiences. I was sitting on her bareback and I said we can take a step, you can do this, you can take a step. And she stiffened and went and I'd never been on a horse that bucked before. I didn't know that was a precursor to I'm going to buck. So having a serious accident really opens up your mind to being really aware of horse body language.

Speaker 1:

For me the big, the big revelation. I was about 15 or 16. And I realized that having a horse who was absolutely obedient is downright dangerous. Because I was working with a horse who was a little rowdy and I was really proud of myself. He listened to me perfectly, he did exactly everything I said, every minute, and I gave him a faulty cue and we landed on top of a jump, on top of a jump and we landed in the heap and I had, I had I don't know how long. I was unconscious because there was nobody else around. And that's when I realized I don't want a horse who always obeys me. I want a horse who thinks for himself. If he'd been thinking for himself, he'd have, he'd have just said we're not doing that job, I'm stopping. But instead he obeyed and it did not go well. So I forever then appreciated a horse who thinks for himself and recognizes danger.

Speaker 1:

And that's another thing you lose when you have a horse who is robotically obedient. They will do things that are dangerous because they've been, they've been so conditioned to do exactly what they're told, no matter what, whether it makes sense or not. So you know actually when, when I was thinking, when I was working with Brandy and and then trying to put together my book, and the focus of my book changed multiple times in the process, but by the time Brandy and I had been working together for a while, I was able to characterize what actions do we take to help a horse feel safe with us and have them want to be with us and then become a partner we can really feel comfortable with and feel confident in, and I characterized five specific things that we can do, so I'd like to just sort of give you an overview of what those are. The first one is what we've been talking about is earning trust, and a huge piece of earning trust is respecting their personal space. You know you'll see people walk up to a horse and, just like, grab the lead line of the reins and expect the horse to walk with them, or grab the reins to seek their foot in the stirrup without even saying hello. And when I meet a new horse, I always introduce myself, and I'm amazed how many people are shocked that I'm ignoring them and talking to their horse. Now, when you meet dog people, they expect you to introduce yourself to the dog. Right? What dog person's insulting? You introduce yourself to the dog first. But horse people aren't wrong with this. Yet we need to introduce ourselves to a horse and that means stop a little ways outside the horse's personal space.

Speaker 1:

His personal space is huge. For horses it matters amongst them. Like you said earlier, they can't gallop together in a herd if you don't pay attention to personal space. So I always look for the personal space and as I'm approaching the horse I look for does he turn an eye or an ear toward me to acknowledge my presence? If he hasn't, I pause and if his body leans away from me, I stop. It's like when you approach people, you know just walk up to a stranger and touch them. That's creepy. So why would you expect a horse to put up with that? So the personal space is really huge. And then, like we were talking about a few minutes ago, the touching. That's all personal space.

Speaker 1:

There were some studies of people grooming horses and Showing that there were a lot of dangerous behaviors because horses were saying I'm not comfortable with this, please don't do that, and people were ignoring it in the interest of getting the horse clean and ready to tack up. So we need to pay more attention to how horses feel about us in their personal space and what we do there. The second we've also talked about is the clear body language. Make sure the horse understands exactly what you want, so that your body language and your wishes are in line. I see this often in videos of people lunging a horse. They're saying one thing and their whip is presumably supposed to be telling the horse something, but their body language is saying something completely different and so, and then the horse is confused. So we up the ante and add more pressure, which makes the horse more confused, and Then we have anxiety. And then we have like the horse is thinking I don't want to be near you, just just put me back in the pasture, go away.

Speaker 1:

Always, always, look at their at their emotional state, and Horses have well, all mammals have seven core emotions. Four of those are positive emotions. There's bonding and Curiosity, play and lust. Of course, lust is not one of the positive emotions we generally want to bring into our relationship in our training. But if we look at the bonding, which comes a lot from respecting their space and but a lot of people miss the curiosity in the play those are huge ways to engage horses.

Speaker 1:

Curiosity is what I call investigative behavior, encouraging horses to Be curious about things. One of the one of the worst things people do with horses, especially with young ones, is is those desensitizing programs when they want the horse to not react when the person brings some strange object toward them. And so now you've become the source of anxiety. Why should this horse trust you? So instead, if we use investigative behavior and engage the horses curiosity, then we let the horse investigate the thing.

Speaker 1:

So, for instance, I'm riding down the trail and there's something weird on the trail in front of us. Do I use pressure to make my horse go past it and pretend it's not there? Then his view of me is I See something I should be worried about, and Lynn is so clueless she doesn't even know we ought to be paying attention to this thing. How do I trust her as a leader? So instead, we see something strange.

Speaker 1:

Look to stop and look at it and Generally, once my horse has looked at it for a while, it's gonna go closer and Maybe he's gonna decide it's really worrisome. If it's really really bad, I might need to have to. I might need to get off and walk up to it first, because, after all, you just go first. Don't they Release good leaders to go first. So okay, lynn, you prove to me that this thing safe and then we can go past it. It in the ring, we can do. We can do even more than that. We can just put out all sorts of different things to let horses look at me with use their curiosity, and when you're associated with curiosity and Discovery and fun things, that's bonding.

Speaker 1:

It's the fourth well, we use learning modes other than pressure and release and, ironically, other than positive reinforcement. Okay, positive reinforcement can be great, but that's those. Those are only two of the ways that horses learn. They also learn through social learning, like we talked about earlier, where the horse is copying what you're doing. They learn by copying other horses and and and watch out, horses can be copying things you don't realize they're copying too. Brandy is a wizard ducking under her stall guard. We can no longer use a stall guard at the front of her stall. We have to shut the door because she knows how to stick her head underneath and zip right out of the stall, and I suspect she learned that by watching me do it sure?

Speaker 2:

Oh yeah, I grew up art. My, my mentor at the farm said don't crawl through the fence, the horses will crawl right through too.

Speaker 1:

I can. I can, I can just picture, especially if you have ponies or a agile small horses, yeah, so social learning and investigative behavior are the are the third and fourth modes of learning that actually engage horses. Intelligence Because positive and negative reinforcement We've decided what we want the horse to do and we're we're Providing reinforcement, either positive or negative, to get the horse to do what we've already decided they need to do. Investigative behavior is Independent learning for the horse. He's using all of his different senses to when, when he approaches, he sees something, he hears it, he smells it. Horses have an incredible sense of smell. They're actually being used for search and rescue Because their sense of smell is so much better than ours and actually, yeah, pretty close to dog.

Speaker 1:

So this now becomes independent cognitive learning. So once I've let a horse investigate something new, it is never a source of fear again because he's observed it, he's Smelled it, seen it, listen to it, possibly touched and tasted it, which is and brandy will go all in Anything new. She's ready to check it out, because new things are no longer scary, new things are more like games. So that's becomes an antidote to fear as well as as a learning mode. And the because curiosity is one of the core emotions. Learning through using the curiosity is intrinsically rewarding, and this is more powerful Than any external reward, any treat that we could possibly give.

Speaker 2:

Fun, oh yeah, I think of how a child learns the same principle is all of us actually. Yeah, okay, so that was the three things. Is there two more?

Speaker 1:

The last one, number five, is protecting horses from unnecessary stress, and we can't protect them from all stress, so I make a distinction. Unnecessary stress is things like waving whips at them, chasing them around, any pressure that we put on them that it doesn't, it doesn't need to be there. But life brings lots of stress, things like that, visits, for instance, new situations and so instead of trying to protect horses from these things, we want to Teach them how to cope with them so that they're more resilient. The more time that we can help them spend in a positive emotional state, then the more resilient they are when bad things happen. So brandy found that it was pretty safe being with me and Nice things happened.

Speaker 1:

We did lots of investigative behavior. We went for walks, we played with things, but you know that's a good thing, um, but you know the vets gonna come, the fairies gonna come, says chiropractor and the dentist, and we need to help them be ready for these events. So I played that, I played fair, your, I played chiropractor. You know, short of doing anything that you know that requires skill that I don't have, but I played with the body parts. I stood up on a hay bale next to brandy or on a stool next to her so that I Was over her back, like the chiropractor does when she's making adjustments on the back.

Speaker 1:

So I Was able to get her accustomed to things like this Over time, without with no pressure. No, no need to like well, we have to get the job done because the vets on a schedule, yeah. So I prepared her to cope with these things and I let them know by mimicking shots, which was a great idea I got from. One of my vets is mimicking shots, as brandy was petrified I mean she choked one time and the vet said give her, told us what to give her an injection of it. We couldn't do it because she was too terrified. I thought, well, this isn't good. So we worked with it and now all of my horses know that after they've gotten a shot or after they've gotten blood drawn, this is going to be a big fat cookie reward.

Speaker 2:

All right, all right. Well, this has been pretty, pretty interesting. I'm, of course, we're all learning a lot from you. Now we're gonna get to the part of the show that we call treat time and the questions, and so Usually I have like cookies or something, but I didn't have time to bake, so I had these beautiful grapes that we're gonna, and if you were here We'd be partaking, but anyway. So that's that's just kind of a nice break treat time and Then we're gonna go right into the questions. Now I sent you An intake form and on it was a series of questions. We copied this idea from work Schiller, who of course you probably know a horse trainer and and podcaster. He actually copied the idea from Tim Ferriss's book tribe of mentors, so we just got to give credit, okay. So I asked you to pick five of the questions of the 20 I sent, and so we'll start with the first one what book would you recommend and why?

Speaker 1:

Well, I would, you know modesty, I'll recommend or recommend mine, because, as I looked around, as I said earlier, many people have the right philosophy of let's watch the horses Emotions and tune into those and make that an integral part of our training so the horses can feel safe with us, because that's what they really want.

Speaker 1:

But I couldn't find anybody any other books that explained how to do it, and that's why I felt this was my. This was something I needed to do was to let me lay this out as as clearly and succinctly as possible, with Brandy demonstrating in photos, bronze doing some of the demonstrations and that so that that people could see most people can do this themselves. At least pieces of this everybody can do for themselves, and I think a lot of women in particular Underestimate their own ability to work with their own horses Because they get caught up in. Well, this guy knows more than I do. He's got he's got all this experience and I've just got this one horse. But Mostly people read their own horses very well and when you tune in, tune into your horses feelings, most women are able to work with them a whole lot more than they think they can.

Speaker 2:

I agree 100%. Okay, what is the most valuable thing that you put your time into? That has changed the course of your life?

Speaker 1:

I was researching for the book when I realized that Brandy was looking to me to help her and I didn't know what to do. I I got busy and, in addition to that very lucky break, I had seeing that young trainer working with the traumatized pony. I also used all of my Equestrian background and all of my academic background to research what have other people done? What if they made work? And then how do we put it together and make it work for us regular people, not not the people who are going to be in the Olympics or doing Shows, but those of us who have our horses at home and we just want to have a good bond and feel safe and comfortable and enjoy the time that we spend with them.

Speaker 2:

I Think that everybody wants that with their horse for sure. Mm-hmm. What is the worst advice given in your profession or a bad idea that you hear of in your field of expertise?

Speaker 1:

Be your horse's boss. Your horse wants to nominate you. You need to be dominant over your horse, because otherwise your horse will take over. I Really start to wonder if this doesn't come from people who are actually afraid of their horses because they're they're so adamant about never let the horse in your space and you have to move the horses feet. Well, no, if my horse is scared, I don't need to move her feet, I need to let her calm down first. Exactly, yes, my horse is always welcome in my space if she's gentle, and this is something horses totally understand. Mm-hmm, in in a horse group. You can go into somebody else's space if you're polite about it. Right, and my horse only gets this. They're always welcome in my space because they know they're gonna be. They need to be gentle, but they also know that when I go into their space I'm going to be gentle. Yeah for sure.

Speaker 2:

Okay, what inspires and motivates you to do what you do and what is your true purpose in the world?

Speaker 1:

I Love to help people figure out for themselves how to be independent and work better with their horses. I'm not looking to have a big following. I don't want to be anybody's guru. So many people really have the right, the right mindset, the right heart to work well with their horses and I want to give them the tools to be able to do it independently and so that they can. They can feel more confident and be safer and happier with their horses. For sure.

Speaker 2:

Okay, the last question what did you want to be as a child and how close did you get to that dream?

Speaker 1:

I I Wanted to be a horse Psychologist. Oh, and I thought to myself as a kid Well, there is no such thing, so I guess I have to do something else, and I'm not coordinated coordinated enough to be a great rider or trainer, so I Guess I have to go to college instead. But you know, it all fit together in the end. Everything that I learned academically relates to horses and and, and I guess in a way I am, of course, psychologist in that the thing that I am most fascinated with is how horses think and feel, and that's where I've been putting a lot of my studying now is taking some of Carolina Westlands courses, because she is is absolutely brilliant at explaining animal emotions.

Speaker 2:

Well then like. I said we and our horses are lucky that that you chose this path. Okay so I'm gonna hold up your book one more time because I'm so excited about this. Where can people find this book? Where can they get in touch with you? I mean, we will include all these links on the show notes and things like that, but if you want to share with us, how do we, how do we learn more about what you're doing and how to find your book?

Speaker 1:

But you can find my book at Trafalgar Square books, which is my publisher, and also an Amazon, and in UK and New Zealand and Australia there's other publishers. I've got all of the the links on my website and it's been translated into Polish and so there's also a Polish Publisher and I've got all those links so you can find more about me on my website. I've got lots of articles and blogs and I post regularly on Facebook and I usually post questions on Facebook and I have a very active Group of people who respond with lots of insight.

Speaker 2:

Oh yeah, I'm quite sure that's how I found you. It was on Facebook, because I follow you and it's always thought-provoking, interesting, worth the read.

Speaker 1:

Thank you, that's my goal, and there's so many people who've had varied experiences and are very insightful, and so when I post the articles and blogs on my website, I often include what I've learned from, from as as they respond to my questions on Facebook. Yeah, it's a cool thing.

Speaker 2:

Well, this has been a great experience I just like makes me want to go work with my horses right now. Try some of the things I'm learning. We're all very grateful for you, linth, for coming on our show and, like I said, we'll have all the information on the web, on the on our website that connects to all your stuff, and thank you again for coming. We really appreciate it.

Speaker 1:

Thanks for inviting me, barbara. It's been my pleasure.